Podcast #2: And Then One Day Everything Changed..

It’s fitting that Abraham Maslow, the man behind the concept of the hierarchy of needs, was born in Brooklyn, the city that has come to define the twenty-first-century brand for living a creative existence. Born in 1908 to immigrant Russian parents, Maslow was raised in a very different Brooklyn. His early years were marked by poverty, anti-Semitism, a toxic relationship with his parents, and a lack of self-confidence, but through a combination of extraordinary intelligence—he was reputed to have an IQ of 195—hard work, and the stability of a happy marriage, Maslow persevered and developed theories that expanded our understanding of the human experience.

Prior to Maslow’s breakthroughs, psychology had focused on what was wrong with people—their neuroses, their mental illnesses. But after witnessing the atrocities of World War II, Maslow theorized that this conventional approach was limited. He created humanistic psychology—the study of unlocking human potential.

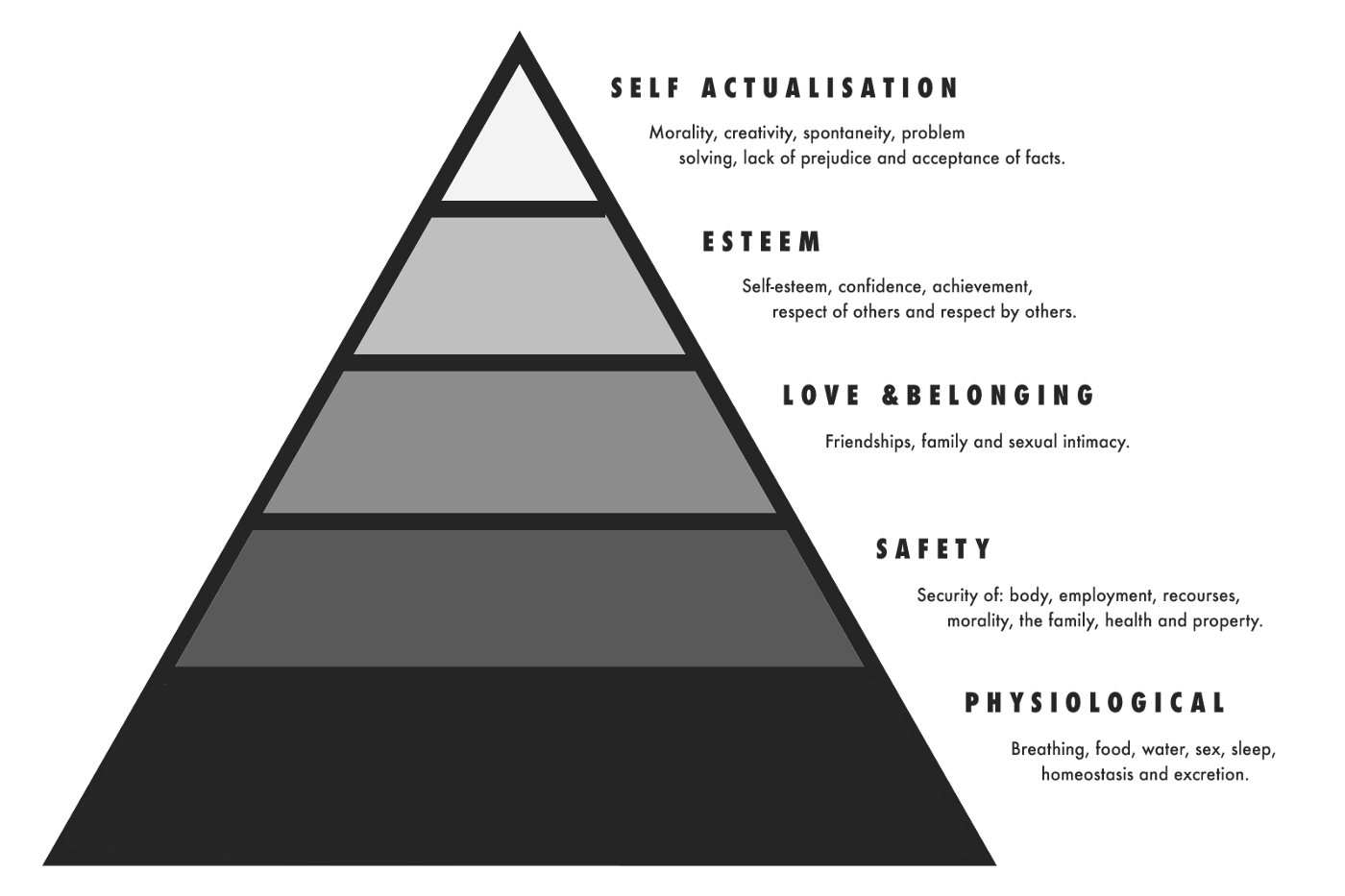

Maslow’s work changed the course of psychology by concentrating on how people could flourish by amplifying what was right about them rather than trying to modify and correct their psychic weaknesses. This cornerstone belief was reflected in his approach to therapy. He looked at people seeking help as clients instead of patients, and strove to establish warm human dynamics with them, not clinical, impersonal physician/patient relationships. With this emotional connection as a basis for action, Maslow then set about working with these clients to improve their lives. He believed every human has a powerful desire to realize his or

her full potential. Maslow’s term for reaching that goal was self-actualization, which he understood as “expressing one’s creativity, quest for spiritual enlightenment, pursuit of knowledge, and the desire to give to society” within daily life. If an individual is able to self-actualize, they become capable of having “peak experiences,” which he defined as “rare, exciting, oceanic, deeply moving, exhilarating, elevating experiences that generate an advanced form of perceiving reality, and are even mystic and magical in their effect upon the experimenter.”

Sounds pretty spectacular, right?

But Maslow also stated that the basic needs of humans must be met before a person can achieve self-actualization and enjoy peak experiences. That means unless you have adequate food, shelter, warmth, security, and a sense of belonging, you’re unable to reach this higher consciousness. Not until the twentieth century had any significant portion of humanity had their basic needs met for a sustained period.

The Assembly Line

The year 1908 not only featured the birth of a man who would take psychology in a new direction, but it was also a revolutionary year for organizations, including the Ford Motor Company. 1908 was when Ford introduced the Model T, the first widely available and affordable consumer automobile. For years, Henry Ford had been maniacally focused on his goal of producing a simple, reliable car that would be financially accessible to the average American worker. But in order to build his dream, Ford realized he needed to eliminate the handcrafted construction process and replace it with a more automated system to expedite production.

The idea for the system Ford needed was introduced to him when an associate visited slaughterhouses in Chicago. These slaughterhouses disassembled animal carcasses as they moved along a conveyor belt. Ford realized he could use this process in reverse, approaching the construction of the automobile as an assembly line, using standardized parts and unskilled labor. This allowed him to radically increase his production capabilities and significantly decrease his costs.

While Ford didn’t invent the concept, he perfected it. Prior to the assembly line’s arrival, it took twelve and a half hours to build a Model T—a slow, expensive process performed by teams of skilled workmen in multiple locations. The assembly line flipped the process on its head. Instead of the workers going to the car, the car came

to the workers, and they could perform one part of the process over and over. Ford was able to reduce the time it took to build a Model T to just ninety-three minutes, allowing him to produce eight times the number of cars in the same time-frame.

The impact of the assembly line wasn’t only felt at Ford—it became a key development in growing the world economy across the twentieth century. Manufacturers were now capable of producing significantly more volume at much lower costs. And with the introduction of unions, workers were paid higher wages for their efforts, creating the consumer base necessary to purchase all the products that were being generated.

While the assembly line created some meaningful advances in society, it widened the gap between the haves and the havenots by solidifying a tremendous barrier to entry for manufacturing businesses. Factories and assembly lines cost millions and millions of dollars to build, and those resources were only available to large organizations and wealthy industrialists. That made it nearly impossible to disrupt or innovate without being associated with one of these entities.

The assembly line also marked a tipping point for standardization and globalization. Prior to its arrival there was a strong emotional connection between the artisan and the product. The maker was close to the consumer, and that meant something to both of them. Standardized production over the twentieth century eroded that connection by separating the producer from the product. Producers no longer had to be skilled—they now only had to handle a piece of the process. That, with very few exceptions, systematically eliminated specialized artisan work. And the more efficient production became, the more financially beneficial it was to consolidate on the retail side as well, which led to what most call globalization, but I call global monotony. We entered the “Boring Age,” one in which different cities and countries all featured the same stores and products.

The best example of this phenomenon took place in the fashion industry. Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Christian Dior, Chanel, Tiffany— these were all individual artisans or shopkeepers, people or families who worked hard at their craft and established a strong business by building a reputation for quality and a direct connection with their customers. During the past century, a majority of these businesses were acquired by conglomerates that centralized production in large factories in third-world countries. The conglomerates then rapidly expanded the retail operations to satisfy growth targets, allowing a product that had once only been available in select markets to be available almost anywhere. Eventually, a name that stood so clearly for handcrafted, one-of-a-kind products became just another shop among a sea of sameness. The experience of traveling to a far-flung location to experience something special or different was gone. Instead, the consumer would just wait for the inevitable sale at their local retail mall to purchase the once unforgettable items for fifty percent off.

The Shift

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

—Isaac Newton

And then one day everything changed; the world shifted on its axis, our consciousness evolved. Instead of making their purchase decisions based solely on price, people became willing to pay more for sustainable or organic products. They no longer wanted their meat mass-produced; they wanted grass-fed beef from a local farmer. Rather than just a good sweat from their exercise, they also wanted mindfulness, so they took up SoulCycle, yoga, or meditation. And rather than settling down to buy their dream home and build their 401k, they spent their resources searching out experiences they could share and cherish more than they would another purse or car. Above all else, they wouldn’t accept the status quo. Instead of working in secure yet unfulfilling jobs, they wanted to create an existence that reflected their innermost desires and beliefs. And they did, in record numbers.

Millennials and The Millennial Mindset

Let’s return to Abraham Maslow. Remember, he asserted that the basic needs of humans—food, shelter, warmth, security, and sense of belonging—must be met before they can achieve self-actualization. And today, for the first time in human history, a large portion of the population is no longer consumed by daily concern for their basic needs.

In one of his recent letters to shareholders, Warren Buffett addressed this:

“Most of today’s children are doing well. All families in my upper middle-class neighborhood regularly enjoy a living standard better than that achieved by John D. Rockefeller Sr. at the time of my birth. His unparalleled fortune couldn’t buy what we now take for granted, whether the field is—to name just a few—transportation, entertainment, communication or medical services.

Rockefeller certainly had power and fame; he could not, however, live as well as my neighbors now do.”

Freed from incessant worry about securing the bare essentials to live, the majority of us in the Western world are able to focus on tending to our higher needs—on pursuing happiness, on thriving. And one group has benefited from this shift more than all the rest—millennials, the largest, most diverse generation ever.

Millennials, those Americans born between 1980 and the early 2000s, spent their youth in relatively comfortable surroundings. They watched as their parents—the Baby Boomers and Gen Xers—obeyed the rules of the industrial complex, getting steady corporate jobs and saving for retirement. Their parents achieved modern society’s definition of success: material wealth. But millennials could see that, rather than bringing fulfillment, this path often ended with their parents unhappy, divorced, stressed-out, or on antidepressants. In response to this, millennials went in another direction. Well-educated and communicative, they learned from their parents’ experiences and adjusted their needs hierarchy to put meaning ahead of money.

Millennials want lives marked by creativity, spiritual satisfaction, expanded knowledge, societal contribution, and multilayered experiences. Sound familiar? We’re in Maslow territory—millennials are seeking to live self-actualized lives and enjoy peak experiences, a generational change that has had extensive repercussions.

The Platform Business Model

As we saw, Henry Ford changed the world by combining his vision for a mass-produced, affordable automobile with the concept of an assembly line. The problem was that the barrier to entry to any industry was so great that only the rich or existing corporations could play, so his system gave the majority of the power and money to the few rather than the many. But over the last thirty or so years, some very smart people in Silicon Valley changed the world yet again. With the Internet and mobility becoming widely available, they created a new way of communicating and doing business centered around platforms.

A platform is a raised, level surface on which people or things can stand. A platform business works in just that way: it allows users—producers and consumers of goods, services, and content— to create, communicate, and consume value through the platform. Amazon, Apple’s App Store, eBay, Airbnb, Facebook, LinkedIn, Pay-Pal, YouTube, Uber, Wikipedia, Instagram, etsy, Twitter, Snapchat, Hotel Tonight, Salesforce, Kickstarter, and Alibaba are all platform businesses. While these businesses have done many impressive things, the most relevant to us is that they have created an opportunity for anyone, even those with limited means, to share their thoughts, ideas, creativity, and creations with millions of people at a low cost.

Today, if you create a product or have an idea, you can sell that product or share that idea with a substantial audience quickly and cost-effectively through these platforms. Not only that, but the platforms arguably give more power to individuals than corporations since they’re so efficient at identifying ulterior motives or lack of authenticity. The communities on these platforms, many of whom are millennials, know when they’re being sold to rather than shared with, and quickly eliminate those users from their consciousness (a/k/a their social media feeds).

Now, smaller organizations and less prosperous individuals are able to sell to or share their products, services, or content with more targeted demographics of people. That’s exactly what the modern consumer desires: a more personalized, connected experience. For example, a Brooklyn handbag designer can sell her handbags to a select group of customers through one of the multitude of fashion or shopping platforms and create an ongoing dialogue with her audience through a communication platform such as Instagram. Or an independent filmmaker from Los Angeles can create a short film using a GoPro and the editing software on their Mac and then instantly share it with countless people through one of a dozen video platforms and get direct feedback. Or an author can write a book and sell it directly from his or her website and social channels to anyone who’s excited about it. The reaction to standardization and globalization has been enabled by these platforms. Customers can get what they want, from whomever they want, whenever they want it. It’s a revised and personalized version of globalization that allows us to maintain and enhance the cultural connections that create the meaning we crave in our lives.

The Result

Now that the barrier to entry has been significantly diminished—no more big factories and assembly lines—ideas, intangibles, and creativity have more value and influence than ever before. This changes what’s possible for the majority of humanity. A talented teenager starts designing clothes in school, creates a following on Instagram, and a few months later ends up doing a capsule collection for Nike, the biggest sneaker company in the world. A singer shares her renditions of covers on YouTube, is contacted by A&R from a record label, and a couple of years later becomes the hottest thing in the music business. Or an engineer shares his idea and business plan on Kickstarter and is fully funded and on the road to building his dream in just twenty-four hours.

Extraordinary opportunity is now available and accessible to individuals and organizations with the creativity, passion, ambition, and work ethic to manifest their ideas. And, coincidentally, this is happening at the exact same time that a growing portion of the population is seeking out and rewarding creators for their work.

Millennials (and those living with a millennial mind-set) support and consume products, services, and content made by passionate and authentic individuals and organizations they feel a connection with. That’s what we call a product-market fit. Except it isn’t a micro-market—it’s the largest market in the world, and that has changed everything.

Welcome to the Age of Ideas.

That’s Great, But How Does This Apply To Me?

You have been born into a time when anything is possible and all the tools to make your dreams real are available and, for the most part, affordable. Your ancestors fought to remove the restraints of monarchy and dictatorship, your parents and grandparents were the guinea pigs who struggled with the limitations of the industrial system, and you are the beneficiary of it all. You now have the freedom to pursue your own path, discover your best self, and connect with a community that helps you proceed along this journey. There is nothing holding you back.

If you don’t have the necessary education, go watch some videos on YouTube and start learning.

If you don’t have an audience, start a social media account and begin building relationships.

If you don’t have the money to pursue your project, put together a pitch-deck and start raising it. Or better yet, bootstrap your project and work on it in the evenings after you finish your day job.

The game didn’t just change—the field got turned upside down and inside out. And most people don’t understand how the new paradigm works, giving those that do an even greater advantage. Your ideas have more power than ever before, and when you understand how to manifest and share those ideas, you can make a substantial impact.

Unlocking that value inside of you is what this book is all about.

I am guided by the belief that everyone desires freedom, fulfillment, and success. All three come from understanding the emotional elements and transforming them into sharable creative expressions. This gives your life and business meaning.

In the modern market, meaning is what generates value, making your creativity the primary driver of future value creation and the last remaining sustainable competitive advantage.

Everything you could ever want or need to start a business and share your ideas is just a click away. You want to start a coffee company? Partner with a local roaster, brand your beans, and go.

From Starbucks to Blue Bottle to the local coffee shop around the corner, the coffee you are drinking is a highly accessible commodity. When you pay a premium for a branded cup, you are paying for the creativity that went into that cup. The store design, creativity; the cup design, creativity; the marketing, creativity; the experience, creativity. The Unicorn Frappuccino is not a miracle of mother nature, it’s a miracle of human creativity and marketing. Everything that makes a cup of Starbucks coffee worth five dollars is somehow tied to the creativity and beliefs of the Starbucks organization.

Bottled water is another example. Free, high-quality water is available in much of the developed world. But the developed world is exactly where the majority of bottled water is consumed. In 2012, in the U.S. alone, we spent $11.8 billion dollars on bottled water.

Because packaging is a fixed price and water is a low-priced commodity, what exactly are we paying the rest of the money for? The answer is that much of the value is tied up in the brand, the idea, how it makes you feel, the creativity.

The point I’m making is that in the Age of Ideas the barrier to entry exists more in our minds than it does in the real world. Differentiation and value today come from unlocking your creative potential, not owning a factory or a farm. The only sustainable competitive advantage left is being the best version of yourself. Manifesting your creativity via sharable forms such as products, services, or entertainment—that produces your advantage. The meaning behind your passion, whether it be for hospitality, law, or hot sauce, now translates into value. In the Age of Ideas this is what the market demands, and you have the power to give it to them by unlocking your unique creative potential.