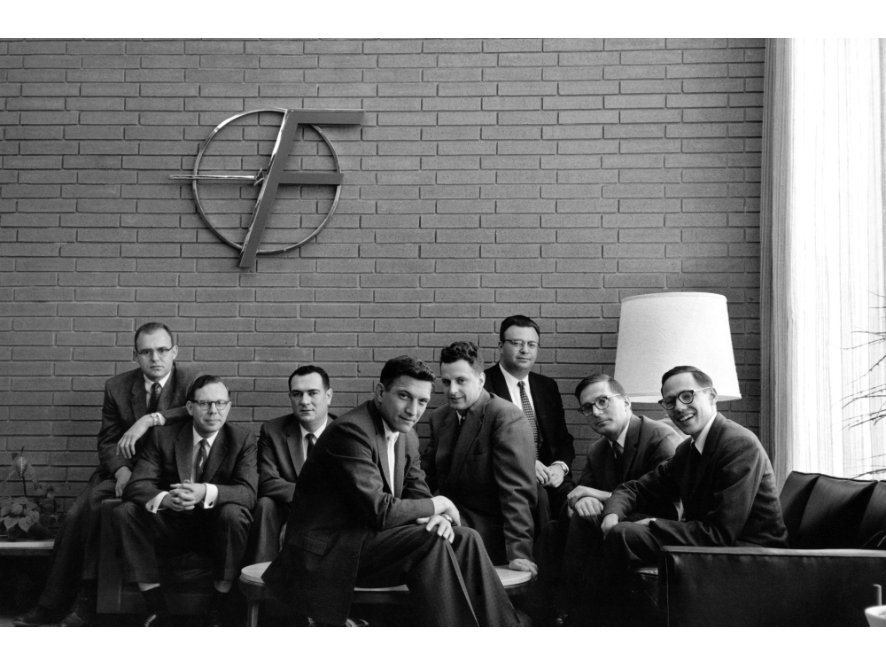

The Traitorous Eight & the Start of Something Big

On a hot summer morning in San Francisco in 1957, eight of the most talented young scientists in America convened for a clandestine meeting at the Clift Hotel. They gathered over breakfast in the famed Redwood Room, a bastion of the city’s old guard. A nervous energy consumed the table, fueled by uncertainty, possibility, and fresh-brewed coffee. The eight worked on developing silicon semiconductors—a groundbreaking new technology—at Shockley Semiconductor outside of Palo Alto. The company’s founder, Nobel Prize–winning scientist William Shockley, was a brilliant but difficult manager: erratic, mistrustful, and impatient. He had even gone so far as to hire detectives to give his employees lie-detector tests, and these employees, experts in a field in which there were few, were frustrated and angry.

After considering numerous options, the men decided they must defect. They planned to establish their own company under the leadership of MIT graduate Robert Noyce, a charming, personable twenty-nine-year-old electrical engineer from smalltown Iowa. Getting Noyce on board hadn’t been easy. He was the leader they needed, but he had a young family, and he needed to be persuaded to leave his guaranteed paycheck for something with no model—creating a new company in a new field based on nothing more than combined knowledge, faith, ideas, and passion.

As Tom Wolfe would later write in Esquire:

“In this business, it dawned on them, capital assets in the traditional sense of plant, equipment, and raw materials counted for next to nothing. The only plant you needed was a shed big enough for the worktables. The only equipment you needed was some kilns, goggles, microscopes, tweezers, and diamond cutters. The materials, silicon and germanium, came from dirt and coal. Brainpower was the entire franchise.”

Brainpower was the entire franchise.

After the meeting, the group’s first move was to approach Shockley’s main investor, Arnold Beckman. Beckman had been arguing with Shockley for months about spiraling research costs. Shockley had threatened to take his team elsewhere and find new money. But the eight scientists knew this was a bluff, and informed Beckman of their plan to leave. Despite a trio of positive meetings, Beckman ultimately said he was planning to stick with the senior researcher.

Fortunately for the employees, they had also contacted other possible investors, including thirty-year-old New York financier Arthur Rock, whom they had written to explain their situation. Their letter intrigued Rock, who was impressed with their backgrounds and experience, and Rock told them he wanted to go out and raise the money necessary for them to start their own company. The scientists agreed, and Rock began by sitting down with a copy of the Wall Street Journal, using it to compile a list of the thirty-five largest American companies. During the next few months, Rock diligently reached out to every one of them, and one by one they all said no. Disheartened, ready to move on, Rock received one last lead. An associate suggested he meet with Sherman Fairchild, a colorful, prominent entrepreneur and investor known for unconventional thinking. Founder of Fairchild Camera and Instrument, the son of IBM’s first chairman, Fairchild immediately recognized a potent opportunity and backed the men to the tune of $1.5 million.

On that June 1957 morning, the eight men didn’t have an official contract, so instead they all signed a crisp dollar bill. One by one, these technology pioneers—Robert Noyce, Julius Blank, Victor Grinich, Jean Hoerni, Eugene Kleiner, Jay Last, Gordon Moore, and Sheldon Roberts—added a signature to their own declaration of independence, framing what would be a history-making choice to work on their own terms, having decided to pursue their visionary ideas inside the structure of a new, innovative company.

With the financial backing of Fairchild, the eight men founded Fairchild Semiconductor in a location just twelve blocks from Shockley’s facility. Long before the term “Silicon Valley startup” existed, this trailblazing operation in Mountain View, California, helped produce technology destined to change the world, and incubated extraordinary talent.

Two of the “traitorous eight,” as Shockley called them—Noyce and Moore—would eventually leave to found Intel Corporation. Austrian-born industrial engineer Eugene Kleiner invested in Intel before starting the legendary venture capital firm Kleiner-Perkins in 1972, a firm that would one day fund Amazon, Google, AOL, Compaq, Genentech, and many others. As for Arthur Rock, he unknowingly gave birth to the multi-billion-dollar industry of tech-based venture capital. In time Rock himself would lead the investment in Apple. To complete our circle, Apple founder Steve Jobs would consider Robert Noyce a mentor, and even, some would say, a surrogate father. Taken together, the original employees of Fairchild Semiconductor can be said to have created or helped create hundreds of new companies and technologies.

A revolution of consciousness and creative capital had begun.

To continue check out our book by clicking here.