Experienced Creativity

Creative agencies are as ubiquitous as coffee shops. Ask any unemployed millennial what they’re doing and they’ll very likely respond they have a creative agency. In a world where the tools to create and share are available to everyone, the definition of what makes creative work high quality and effective has become unclear. After all, if you have a novice understanding of Photoshop, a Squarespace account, and a few hundred social followers, you can start your very own creative agency right now. While this shift is incredibly empowering, like all blessings, it’s also a curse. Creative work presented without consideration is magic’s kryptonite; the more bad magicians there are, the more skepticism there is about the value of creative work. Manifesting magic consistently requires a more refined skill set and approach, one developed over time through practices and systems similar to those of a great athlete, trader, or violinist. I call this brand of creativity experienced, and define it as the ability to manifest consistent, high-quality creative outputs over a long period of time.

As a chief marketing officer, it’s my role to source, hire, and manage creative agencies. This gives me a unique perspective on how these entities operate and what differentiates the greats from the not so greats, the experienced creative from the amateur freelancer. The democratization of creative and communication tools has made the ability to define and determine the value of creativity extremely difficult. But the ability to differentiate the good from the bad and find the experienced creativity is a critical element of the magic formula. For example, I recently negotiated a very well recognized global agency from an initial proposal of $2.5 million to almost $500,000 with little to no change in their scope of work. How is that possible? What were they charging the other $2 million for? Was it all profit? Creative agencies sell a product that’s almost entirely intangible. That makes it worth only what the buyer is willing to pay for it, as arguably there’s no fixed cost to providing the service other than their overhead, which is entirely within their control. Yet creative work is more powerful and valuable than it ever has been before. The power lies in the creative applying their experience and talent to your problem. What’s that really worth? It’s entirely dependent on how much solving that problem is worth to the entity purchasing the service.

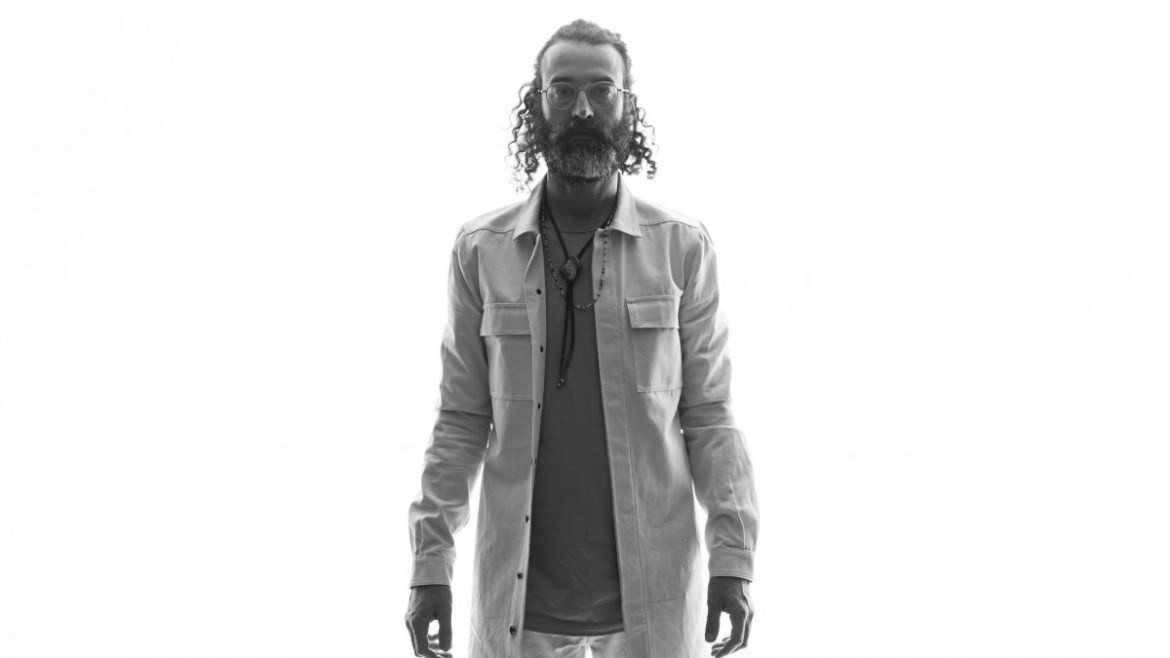

Harry Bernstein is an experienced creative. He’s been changing the world with his mind quietly and consistently for years. Harry—or Harry Bee, as he’s known—is the chief creative officer of Havas New York, an agency that acquired him along with his digital agency, The 88. Harry is deeply intelligent, highly emotional, and overwhelmingly passionate. His speech is quick and choppy, as his mouth struggles to keep up with his mind. His heavy New York accent is a prelude to his deep connection with the people and culture of the city. In recent years, all this has combined with marriage and fatherhood to make Harry his best creative self. His years of struggle both personally and professionally have revealed a polished gem, a New Age digital philosopher using content, strategy, and creative expression—colorful clothing and an ever-growing beard—to share his beliefs with his myriad of followers.

Harry and his team were a major force in the return of Adidas to relevance, launching the incredibly successful NMD line and overseeing the marketing for the Adidas Originals brand. He has also applied his talents to work for Coca-Cola, W Hotels, Belvedere Vodka, Bloomingdale’s, Y-3, the CFDA, Supreme, Pace Gallery, and L’Oréal among others. But he wasn’t always a cultural rainmaker. Harry started out like most of us, as the child of a blue-collar Italian mother and father in Queens, New York. His father was a truck driver for the Department of Sanitation and his mother was a secretary for the Department of Education. He got a lucky break his senior year of public high school when he got accepted into a program that allowed him to get “real world experience” working for an advertising agency. From there, he went to FIT and the School of Visual Arts to continue developing his creative skills.

Harry worked for over a decade in the agency world. As he explains, “I began my career in traditional advertising. In ’99, I worked at Ogilvy & Mather, which is a very big ad agency, working on clients like IBM and AMEX. Very blue chip stuff. Then I quit doing traditional advertising, and worked at Berlin Cameron which, is a small, traditional advertising agency, working on things like Boost Mobile. We did a lot of stuff with rappers, Young Jeezy, Fat Joe, Eve. I did Vitamin Water’s first TV campaign before they were bought by Coke. My final big client there was Belvedere Vodka, and I did a campaign with Vincent Gallo. After Belvedere, I wanted to try something different. I was actually in Atlanta with Young Jeezy, we were talking about Belvedere, and he was like, ‘Harry, my fans don’t care about ads. My [followers] look at me in the club. [Me] drinking Belvedere in a club—that’s going to do more for you than a TV commercial. They want what I do, not what’s in these ads.’ I thought, ‘Oh, that’s interesting’. I had never thought of it that way.” In 2010, he decided to launch his own agency, aiming to capitalize on the potential of the digital landscape, specifically combining content and strategy with digital distribution channels to “identify trends in consumer behavior and align brands with them. Building brands within culture, not outside of culture.”

If you met Harry in the first half of his life, the success he’s now discovered wouldn’t have been entirely obvious. He has always been different, approaching life with his own point of view and testing what worked and what didn’t for him. Harry has always stood out and now stands out as an executive by embracing his true self. He’s made a conscious choice to be himself above all else, which is reflected in how he operates his business; from on-site farmers markets to encourage his employees to eat healthy to holiday parties with performances by classic rappers like Mase and Ja Rule, Harry is approaching his work with his own style. As his mentor Richard Kirshenbaum explained it, “One of the first great lessons I ever learned about being creative is that if you don’t embrace who you are and bring your own accent or flavor to your work, you can never truly be creative, authentic, or original.” Without a doubt, Harry is an original.

While this may have been one of the first lessons Harry learned, he’s learned many others over twenty years as a creative professional. And those lessons, that process, is the difference between creativity—a talent we all possess—and experienced creativity, the ability to consistently and professionally manifest creative output over a long period of time. You see, every creative project Harry works on was a lesson, one that makes him more attuned to the subtleties of his process and the needs of his work and his clients’. He began to inherently understand the types of people he wanted on a project, how to deal with people who just don’t get it, and when to open his brain to relaxation so he could welcome new ideas and inspirations. And as he became more attuned to those needs, his brain became better at putting the pieces together and connecting seemingly unrelated elements into new ideas. He also became better at putting together the elements and people who would create the best conditions for turning great ideas into magic.

Harry shared with me his four pillars for creative success, what he feels has helped him evolve into an experienced creative: mindfulness, inspiration, sacrifice, and empathy. These pillars are the core of his creative practice and have helped him hone his vision and quiet his insecurity. They’ve enabled Harry to “build a life that creates the opportunity to do great work.” As he says, “what you put in, you get out,” so your inspiration, which he describes as what you consume through your ears, your eyes, your nose, your mind, and your mouth, must be considered because it’s the fuel for whatever it is you intend to put out in the world.

Harry combines this “inspired consumption” with a mindfulness practice that helps him connect more deeply to his inner self. He does this through meditation, allowing him to be “more in the moment and connected,” to get more out of his interactions. “Without meditation, I think you are just a robot. You aren’t absorbing anything, you’re just reacting to messaging being pounded against your eyes, ears, nose, mouth and tongue. Focusing on that, and grounding myself; things start to stand out more.”

He combines these pillars in practice with sacrifice and empathy. His mentor, Michael K, taught Harry the value of sacrifice. Michael used to tell Harry “do what you have to do to do what you want to do.” Harry explained to me that he feels you must give things up in the short term to get want you want in the long term. There’s no gain without sacrifice; you’ll never do the work you truly want to do if you don’t develop the skill set you need today. This led Harry to the core of his philosophy, that “ideas come in the doing, learn it, to know it.” Meaning your experiences have a significant impact on your ability to create great work, to expand what you’re capable of. You don’t have to do every job every day, but you must experience something a few times to deeply understand what’s going on and how to make it better. For example, you can’t communicate effectively with a designer if you can’t understand the designer’s perspective, and you can’t sell sneakers on the streets of New York unless you, yourself, have spent time buying and selling sneakers on the streets New York. To understand the perspective of another person, you must empathetically experience their world; you must connect to their emotions and walk a moment in their kicks.

Like shooting a basketball or playing a guitar, being creative—the miracle of forming something new and valuable through action or thought—must be practiced, no matter what the medium of expression. Michael Jackson didn’t just wake up one day and create 13 number-one hits and sell 400 million records. And Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart didn’t just produce 600 works overnight and suddenly become the most prolific and influential composer of the classical era. They learned and they worked, they failed and they eventually succeeded. When I refer to experienced creativity as a critical part in manifesting magic, I’m pointing to the need for creativity that has been persistently practiced through years of experimentation and, if lucky, nurtured and encouraged by the surrounding environment.

Experienced creatives have developed the ability to manifest their breed of creativity consistently over a period of time. Simply put, that’s the difference between a one-hit wonder and Michael Jackson. Anyone can get lucky once—come up with a great idea, write a great line, hum an interesting tune—but to manifest your magic, you must be able to produce consistent creative results over time. The secret recipe for this rare skill is to develop your systems and instincts while still being able to see the world with the naïveté and wonder of a child. Sharpening your sword, but using it to make love, not war. You must have all the information available but be willing to go against the prevailing wisdom, to be wrong at times, to embrace your fear, or, as my wife says, “not give a fuck.”

Being an independent thinker is the opposite of what we’re taught by most organized groups, from preschool classes to our teams at work. We feel comfortable in communities, so we encourage the group dynamic and fitting in above individuality. But creativity and innovation require that you trust yourself and go against the group, that you think for yourself. Nothing truly innovative, visionary, or creative has ever come out of a group of people sitting in a boardroom giving their opinions on an idea, especially when the market is demanding authenticity. Generally, great new ideas don’t come from large companies. As Harry explains it, “Build your own world. I don’t care about the numbers game…. Most of the people copy and emulate to get popular. As a young professional creative, don’t go for the numbers, create your own point of view.” Trusting yourself enough to go against the grain, to do something that’s truly a reflection of your purpose, isn’t what we’re taught. It only comes when we’ve gained enough experience to choose our own path, trust our instincts, and create from within. That’s what it means to be an experienced creative.